I Fear My Pain Interests You

by Stephanie LaCava

Verso Fiction, 192 pp., $17.29

The Rabbit Hutch

by Tess Gunty

Knopf, 352 pp., $17.58

Our Missing Hearts

by Celeste Ng

Penguin Press, 352 pp., $21.49

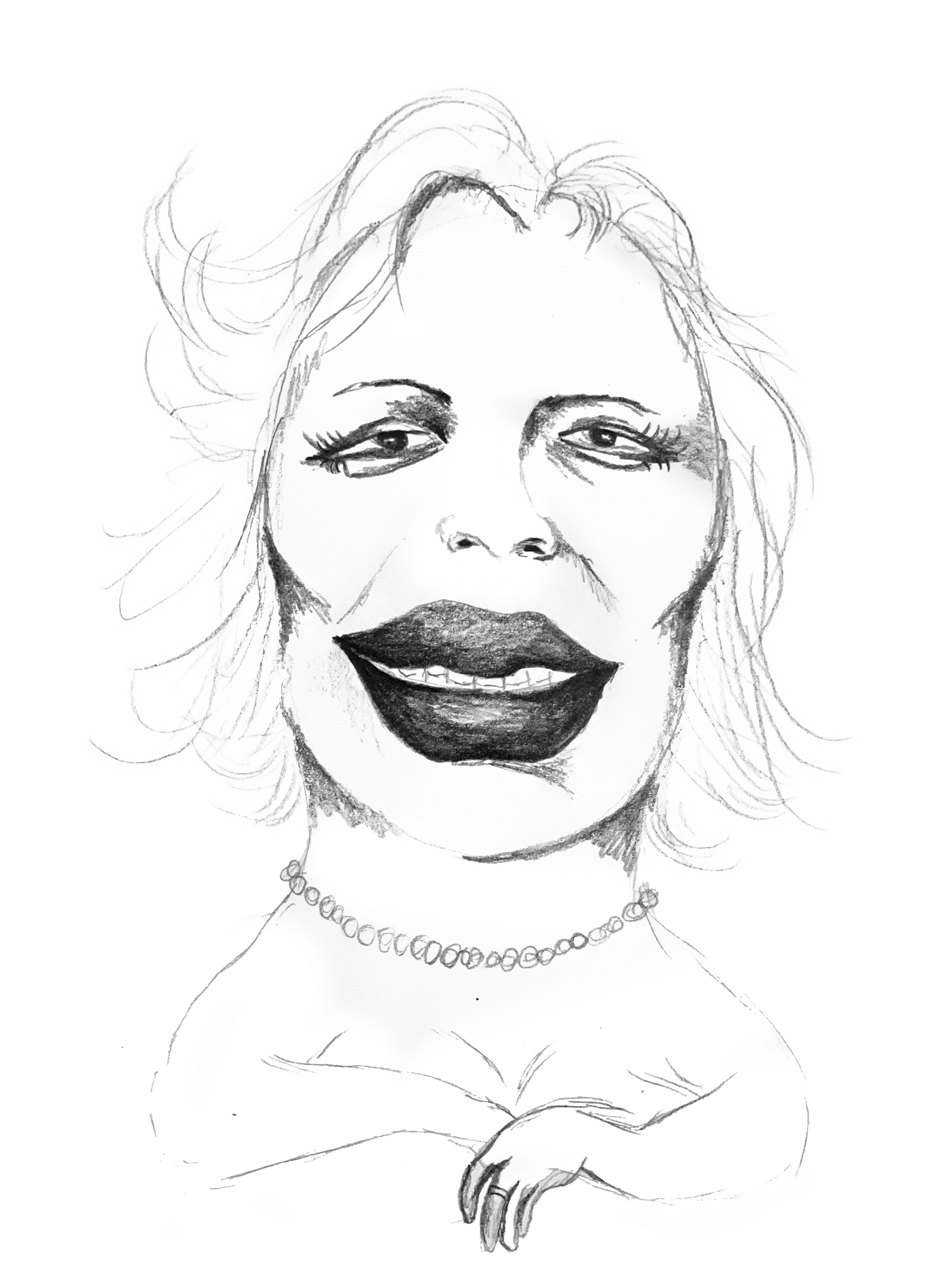

Aesthetica

by Allie Rowbottom

Soho Press, 264 pp., $16.00

Anna, the narrator of Allie Rowbottom’s debut novel Aesthetica, desires the 21st century American dream—the influencer life. A few years out of high school and wasting time in her hometown of Houston, Anna “had reason to believe I could touch stardom, the money that came with it, as a model on Instagram.” Like millions of young American women seduced by influencers, Anna yearns to do the influencing, and transform herself in the process: “[T]he longer I looked, the more I wondered if image alteration might actually be empowering. For women, so often robbed of agency, was there freedom in controlling how the world consumed our bodies? My final project for that Photoshop class was my own image, edited every which way. A smile where there’d been a frown. Smooth skin where there’d been acne scars. Absence where there’d been fat and flesh. Yes, it was empowering to decide which version I preferred.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mars Review of Books to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.